Nikolay Kozakov

DIARIES

1962

Москва, 2016

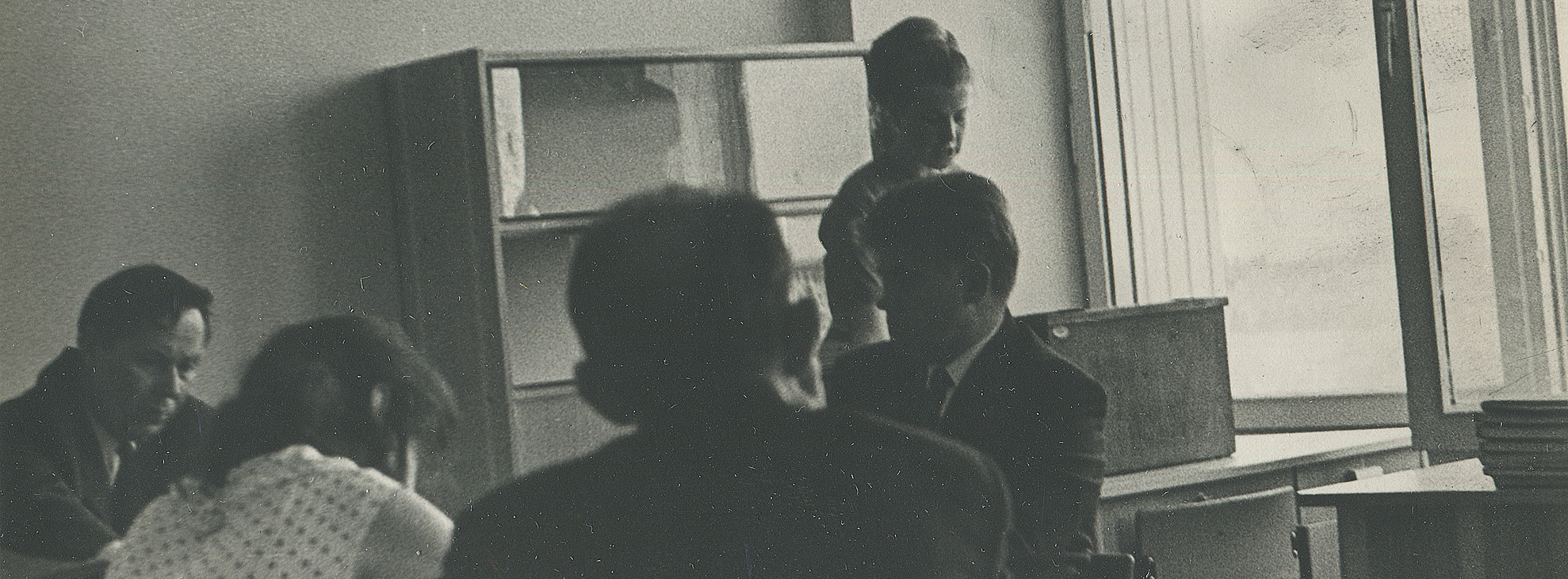

1970, Zaprudnoe. N. Kozakov

Translated by Ben McGarr

Evacuated from besieged wartime Leningrad, ten year old Nikolai Kozakov finds himself in the village of Tolba, near Gorky (now Nizhny Novgorod). His mother, a former teacher, finds work as an accountant in the local children’s home, while Nikolai goes to school, later enrolling on a distance learning course with Moscow State University’s history faculty. The Kozakovs then move to the neighbouring village of Kadnitsy. Nikolai gets a job driving a lorry, and briefly goes off to work on building the Chelkar oil pipeline in Kazakhstan, though he soon returns home.

Kozakov keeps a methodical record of his life. Starting at fifteen years of age, he writes his diary: detailed notes penned in 96-page standard exercise books, each entry beginning with air temperature and wind direction, describing occurrences at work and at home, and switching back and forth between musings on love and his place in society. Separate accounts detail the weather and “Accounts of expenditures and libations to Bacchus”, in which daily expenses and capacities of alcohol imbibed are given alongside the places and circumstances surrounding the drinking sessions concerned. Kozakov writes poetry, later to be published in local small newspapers. When he gets hold of a camera, Kozakov takes pictures, not only of the customary social events and portraits, but also of landscapes, “architectural compositions”, and even a series of “Signs of animal activity”: “Bear tracks with a size 45 boot, 25/7/71”, “Trees gnawed by beavers (old), river Lamna, 26/8/71”. In the mid-sixties, Kozakov breaks off his customary diary and begins a new series of exercise books: Diaries of Hunting and Fishing.

Glushchenkoizdat have come into possession of Nikolai Kozakov’s notebooks for the year 1962. Following extensive work on their transcription and preparation for print, the publishers present the present volume for the edification of readers, in conjunction with a radio drama. Publication has been timed to coincide with the publishers’ summary exhibition Our days are rich and bright.

The publishers hope that, after having lain many long years in a private archive with little chance of publication during the period of state control over literary production, these journals will finally be able to find their deserved readership today. Reading this literary and historical document should contribute towards a better understanding of those bygone “days” themselves, as well as act as a fitting antidote to that nostalgia-prone perception of the past fostered by the family albums and postcards that have been passed down to us, with all their smiling factory workers and imposing views of empty thoroughfares taken in the early hours of the morning.

OZON, 729 RUB

Nikolay Kozakov

Diaries. 1962

170 х 215 mm

624 pages

ISBN 978-5-9906255-3-2

Edition of 1 000

Gluschenkoizdat, 2016

REQUEST, 35 EUR

Nikolay Kozakov

Diaries. 1962

Radioplay

2 x LP

88 min 41 sec

8 pages booklet

Edition of 3 00

Gluschenkoizdat, 2016

10th January 1962

Wednesday

Kadnitsy

I got up before nine. It was foggy outside, with a frost of minus 8, quiet and nice. I had breakfast, drank some coffee and shuffled of to work. I didn’t go through the forest, as I had done previously, but through Zaprudnoye, to go to the shop. I wanted to buy some fur gloves and a ballpoint pen, as this one, and the other, doesn’t write very well, drying up all the time. But they had neither in stock. I then went to the grocer’s, where I bought a bottle of vodka, some herrings, and a loaf of bread. I had promised some time back that I would go for a drink with Sashka Farafontov, now the RZhS fuel transporter. I had to go today, while I had the money. I turned up at the RZhS at ten thirty. A Zhigulnik AYa 88–40 that I had once worked on, before it had been sold on to some kolkhoz, stood in the middle of the courtyard on three wheels. The left part of its bumper had been bent in, the mudguard was twisted out of shape, and the left centre pin of the front driving axle was smashed to pieces; the attenuator rods were broken, along with the break hose, the footboard was scraped, together with the accumulator boxes, the gearbox was dangling underneath the vehicle with the cardan joints, and a wheel stood off to the side with wheel-hub. The auxiliary tank was all deformed too, and the engine, pulled up by the bolts, was lying on the ground in front of the vehicle. A crowd of curious onlookers had gathered around it. They said that yesterday, somewhere over near Rabotki, it had had an unsuccessful “trial of strength” with a lorry. The lorry-driver, they say, had climbed out of the cabin, shook his head, and walked off, as though nothing had happened. I found Sashka, and we went to the oil depot where we had our drink.

He complained about his salary and said he wanted to go away and try his hand at logging in the Urals. I then wandered aimlessly around the workshop and garage. I went into the sovkhoz office to find out if they were paying wages. The thing was, a certain Steklov works there, who had worked with us at the SMU a year ago, as a security guard. Back then, he had borrowed twenty roubles off me — two chervontsy. He gave Mama back a fiver sometime in April. I’d been going to him all summer then, and he kept promising to pay me back, but never did. In late October, I finally went to tell the sovkhoz about it. They promised to remind him. He gave another fiver to Mama on pay day, actually, and I went and looked everywhere for him after that, but couldn’t find him. I’ll have to watch out for him again on payday, the swine. There’s conscience for you! Give with your hands, and you’ll walk with your legs, as the proverb says.

Towards the end, I decided to have another adventure, which I had long been ruminating over. In the Druzhba kolkhoz garage, there were some obviously spare signal lights for a Pobeda which needed expropriating, taking from the car. To bring this intention to life, I got into the model 69 and lay in wait there until everyone had gone. But the damned kolkhoz Stakhanovites, who usually hang around with nothing to do and knock off at three, were not taking the Mick for once today so I lay shivering there inside the car until sometime after five. If I’d been able to get out of there I would have run off, no question about it. But my escape route was cut off. I had to wait. Finally the dickheads finished, turned out the light and left, locking the gates. I waited a while and climbed out of my hiding place. The most annoying thing was how dark it was. I could barely tell the cars apart from their silhouettes. Luckily, the driver had taken the signals off earlier and placed them on the car’s front panel. If it hadn’t been for that, I wouldn’t have been able to detach them in the damned darkness. I needed a relay switch for the tuneable signals. I turned on a torch, but this car didn’t have one. Fortunately, kolkhoz Druzhba had left almost four cars at my disposal. I had to cut the relay out of the ZIL. On finishing this operation, I opened the gates from inside and scarpered, like a thief in the night. And no matter how many times I swear off thieving, whenever I see some good thing in the state’s pocket — my guts start to ache. I just have to take it. Well, sod them. The kolkhoz will write it off. When I got home I had a nap, shaved, and ate supper. In the evening I drank tea and read The Twelve Labours of Hercules. It had got quite warm — 5°. Tomorrow I will have to go round early, to witness the drama that’ll take place in the garage at 8 am. Those guys will be spitting mad…

Zaprudnoe, Moscow. Part One

16 pictures, 1970

11th January 1962

Thursday

Kadnitsy

I got up at seven. The wind whistled outside. I went out and looked at the thermometer. It was 14°. With a strong south-westerly wind and a blizzard this boded nothing well. After drinking a mug of coffee, I tottered off for Zaprudnoye. I decided to go through the forest, but, everything be damned, there was already a lot of snow. When I got to the RZhS, I immediately made for the garage, but had already missed the start of the performance.

An oppressive silence reigned in the garage. By the light of a single bulb, a dense crowd of robbed kolkhoz-workers stood silently in the midst of the room, between the cars. My greetings produced a single gloomy “hiya”. Clearly, the chumps were trying to figure it out — how did it happen? They’d locked the garage doors, unlocked them again in the morning, so how could the signals have gone? I unlocked my car, took the carburettor and went to sort it out in the engine section. I took it apart, blew through it, washed it out, changed the intake connection, and put a new one on it from Sukhanov’s car. This, heating up the manifold, had melted the limiter. I put in the old limiter and changed the connection. I then rooted around in the garage for some bits and bobs. The men still hadn’t been able to make sense of it — they were so shaken by my sacrifice to Hermes, the great Protector of thieves. At around twelve, I fled the site of labour. There was nothing to do until Semyonov’s arrival. May a thunderbolt strike him. I went back via Zaprudnoye. I went to the shop for something to drink — vodka and a St. John’s wort liqueur. I took a tin of grape jam and some gingerbread. It was more interesting walking through the wind than it had been in the morning. At home I tidied myself up, and started peeling potatoes to fry with some meat. The meat — 3 kg of it — I’d got for three roubles back on the 17th December, and it was still lasting me. I remembered how — back in Gorky in 1960, when I bought ready-made beef steaks in Kulinariya — it cost 28 roubles — which was thought incredibly expensive; mincemeat was around 21 roubles a kilo, and Moscow chops — 15 a kilo. And now we have full prosperity, worthy of the dawn of communism as per the programme of the 22nd Party Congress, — if you please, three kilos for a chervonets (and you can eat for a whole month).

Once I’d eaten, I started reading Greek mythology, drinking strong tea with aromatic grape jam. In the evening I listened to the radio, read Knowledge is Power. I wanted to go to the pictures, but they were showing a shitty pro-communist film — Little Bird, about kolkhozes and the like.

20th January 1962

Saturday

Kadnitsy — Kstovo

I got up today at seven with great difficulty. The alarm clock rang loudly but I only just heard it, as it seemed to me like some mosquito buzzing somewhere. Somehow I got up, washed and had breakfast. I left the house at quarter to eight. When I got to the RZhS, Semyonov was in the garage. But being the first to arrive was quite an achievement for me. Sure, Vanka was there, and Groshev soon turned up too. We decided to start the car up. We hitched it onto Sukhanov’s car and towed it out of the garage. Semyonov then sat personally behind the wheel, with Kolka towing him. The wheels span in different directions at first, and then the motor started to spin but without starting up. It only got going after making two circuits around the site. Water was pouring out of it. Semyonov gave the order — seal the carcass, replace the ruptured fuel pipe and so on — and he left for Kstovo. Soldatov went with him. Me and Groshev set about the job. First we had to get it over the pit in the garage. A kolkhoz car was parked there. Then we coupled it to the 69er from the rear, and I pulled it, and it moved. Then we had to find an extension cord. It was useless, the whole day was pretty much a waste of time. Kolka couldn’t pull anything off with the pipe, and I couldn’t fit the attenuator rods. Nothing worked, whatever we tried. We needed four bolts to secure the rods in place, and there were none. Those we did manage to find were no good. And that damned lathe operator — attached to our SMU — dithered like a whore. I was almost begging him on his hands and knees for the bolts. And we did nothing else at all.

The car stayed over the pit and us and Soldatov who turned up at that point went off to the boiler room. It was one o’clock. I argued for going home, but it seems Semyonov had told us to wait for him. We sat and talked. And at quarter to two we went home. Semyonov didn’t come, and we weren’t counting on waiting any longer than we had to for him. Groshev then got in Lyskov’s car that had been at the RZhS for three days, — and broke the right rear axle tube off, and the entire half axle and wheel flew off. I went off at a funny angle past the dairy plant, over the river. I walked a long way and was worn out. It was a hard road, though traffic-compacted, but it was wet and slippery, and I was in padded trousers and felt boots — well, I could hardly walk. I got home, shaved and washed. Mama said nothing — does she have any inkling of where I go off to or not? After cleaning myself up, I had a good dinner, drank compote and went off wieder. The third day in a row of fifteen kilometres!

I arrived in Zaprudnoye around half five. A short way along the lane, I saw a Škoda driving towards Gorky. A small bus was parked up at the stop. I’d only just got onto the highway when it set off. I waved it down and got on. It was from Kstovo, but why hadn’t it stopped as long as it should have? The driver sped off at an incredible rate, driving at 80 all the way there. We were going for 18 minutes. On arriving in Kstovo, I decided first of all to go to the canteen to drink a beer. It turned out, however, that they only work until four on Saturdays, and had shut ages ago. I then went to the shop. I took two bottles of white dessert wine and two bottles of beer, drinking one there and then, I was that thirsty. To eat with it, all I got was some jam, as I didn’t really want to eat and only had a little cash. Butter has turned up in Kstovo, and in bulk, and nobody’s buying it any more. I went to Nastya’s after the shop. On the way I bumped into Raya Rysina — a fortunate coincidence, actually, as I didn’t want to go there alone, so I asked her to go and see what was going on.

Nastya happened to be having a bath, so she asked me to wait a little. I went to the chemist in the meantime — I needed some shaving cream, but they didn’t have any. I walked around half an hour, — it was a wonderful evening, dark and quiet — and I went back to the house. I looked — there was no light on at her window. I wondered if she’d come out to meet me or gone to the Rysins. I went up to Zhenka’s. She wasn’t there. Zhenka asked me how things were going. I decided to go straight. I went round the house, and the light was on. I went in. I crept quietly along the corridor so as not to be heard by the neighbours. Nastya was sitting at the table, with her hair still wet. I asked where the kid was. Turns out he was playing out. I found out later from conversation that she wanted to send him to her brother in Lukerino, but she’d took too long and hadn’t managed it. She just wanted to drink tea. I suggested something a little tastier and took out my bottles. I’d kept one of the wine bottles tucked away, just as well actually, as then her flatmate Lyoshka, a lad of twenty-five, emerged from the bathroom. He lives here with his wife, mother and child, and those lot, Rufka and her husband, live in another flat alongside this one. They dropped in for a shot. Then the kid came too. We all drank, and Lyoshka left. Then I took out the bottle I’d kept hidden. Nastya is clearly no novice at drinking, just like me, sinner that I am. We drank then for a while, with little breaks. The kid ran off somewhere to watch television, and we embraced a little. Then he came back in, asking to go to bed. Nastya tucked him in and turned out the light. While there was still some wine left, we sat in the bedroom. Nastya’s body smelled of something in particular, after the bath… She was wearing a dressing gown, which I then unbuttoned completed. She nestled into me, and I kissed her neck below the hair from behind. We sat like that for a while and then went into the kitchen. The neighbours were already asleep, so there was no worry of anyone coming in. We almost didn’t speak. She sat on my lap, placing her arms around my neck and pressing her cheek to my face. It was quiet, with a soft light coming in from outside, reflected by the snow. A monotonous dripping sound could be heard from the bathroom. My right hand could feel the warm tension in her hips, her mouth breathing no less hot in my face, and her whole body seemed permeated with this heat of desire, but I, in the intervals between kissing her breasts, neck and face, expressed my feelings and she said — “Why? What for?” — as if she didn’t know herself.

Around twelve we went back into the bedroom. I picked up the sleeping boy from the bet and carried him to the couch. Nastya came to me, embracing me strongly, pressing up against me and began to kiss me so hard that my lips began to ache. I experienced all of her, all her body. The salty taste of her lips, the smell of her hair. Women are such astonishing creatures! I’d only known her two days, but it already seemed to have begun so long ago. And she was already like a loved one to me. How they conquer with their fragrance, cleanliness and precision. And a slovenly girl, even if she’s a beauty like La Gioconda, you still wouldn’t think of approaching her. I, for example, find it repellent. A negligent woman prompts disgust. And how precious must the women of the ancient Hellenes have been, so slim and slathered with perfumes!

We lay there, holding each other tight. Our hearts beat as one. Nastya’s hair was spread out across the pillow, her bosom heaving regularly. Our coming together was, in the words of Gábor Goda, both spiritual and corporeal. Fatigued by the sunless night, we slept soundly, sated by love and kisses.

18th March 1962

Sunday

Train № 37 — Moscow

Today was warm and wet, with a little snowfall. A wind was blowing quite unpleasantly. I slept so badly in the night, it was just awful. Or am I not used to sleeping in trains anymore?

We got up just before eight. The attendant came in and woke us. We washed and tidied ourselves up. Our hangovers were dealt with by two shots. Then we looked out the window. I even wrote a little in my diary.

At nine o’clock we pulled up to the platform at the Kursk Rail Terminal. We got our things together and went out onto the square: first of all we had to go to the Kazan Terminal and hand over our stuff so we wouldn’t be having to drag it around. We took a taxi. The driver took us directly to the luggage locker. We handed everything in and went to find out what the deal was with the trains. We decided to take the express № 14 to Tashkent, which goes daily and departs at 19:40. We didn’t go for the tickets yet. We went to the barbers in the station and got our hair cut.

From there we went first to Shmidtovsky, where Aunt Natasha used to live, now home to Tanka and little Natasha. I bought her a teddy bear in Gorky for 5.20 and was now lugging it along like a fool with his sack. We boarded the Metro. I hadn’t been to Moscow for seven years now, and so was a bit lost. I soon figured out what was what, though. We went on the Metro to Krasnopresnenskaya, and then took the tram to the new development where Tanka lives.

We arrived. She was in. When she opened the door, she almost fainted from shock. Then, as you do, she began the questioning. I told her to call on her aunties so they would come over and then I would tell everything. But now we were going to see the sights. And I went to give the bear to Natashka. Tanka’s girl is lovely, such a little doll, simply wonderful. I couldn’t take my eyes off her. She reminded me a great deal of my Galka. And this one is growing up without a father too. Poor children. This is Natashka’s eighth bear (I bought it specially, she really loves them), and she has now started to run around everywhere with them. My friend and I, having promised to come at two o’clock, went to roam. We wanted to go to Red Square first, but decided to go eat and drink beforehand in preparation.

I fancied the Metropole. That’s where we’d decided to go. So we got on trolleybus number five at Krasnopresnenskaya Zastava and rode as far as Sverdlov Square. From there we walked to the Metropole. Some attentive doormen took our coats and led us into the hall. Above there was a cupola with stained glass, and in the centre of the hall — a fountain.

As we entered, I immediately noticed the Americans sitting at the far table. They were talking loudly, not paying attention to anyone. I wanted to sit nearer them to listen and study their pronunciation, but then we decided to take a table at the opposite end of the hall. There then came up to us a nice young man in a bowtie to give us the menu. We immersed ourselves in the study of this document. All the names of the dishes were written in Russian and English. There aren’t many Russians in the Metropole, it’s more for foreigners. And now there were a multitude of North and South Americans, Englishmen and others all rubbing shoulders. Many of them had huge badges on their chests — the symbols of some representative office or mission. Little flags were placed on some of the tables, with the stars and stripes among others. From the vast assortment on offer in the menu, we selected the following: 200 g of Otborny cognac, 300 of Madeira and 200 of Muscat; one crab salad and the Metropole house salad each, a portion of cheese and two natural beef steaks. The polite waiter recommended that we order a lemon, which we did. We drank the first shot with a reverential genuflection, as is the custom in the temple of Bacchus.

A noisy group were sitting beside us then — two Georgians, two Americans and an Englishman. The Englishman was rather reserved and polite, but the Americans, noisy and merry, gesticulated expressively, explaining things to the Georgians, and drank Stolichnaya. Some other Yankees joined them, along with some Chileans. I remember one Chilean in particular — a tall, red-faced brunet in a grey hat with wide sideburns bent sharply upwards and pointed yellow boots. One of the new Americans took several pictures of his colleagues with some kind of special contraption with a flash lamp, which produced the picture, just one of course, after one or two minutes, still wet, directly from the device.

While we were still only a little tipsy, we just peeped across sheepishly, but then, once we’d summoned up a bit of courage, we went to look at it directly. The photographer was surrounded by five waiters too. While it was producing the latest print, I threw in several interjections in English. I couldn’t wait to come into contact with our trans-oceanic friends, and here, finally, fate brought it right to me — one of the Americans came straight up to me and Kolka, put his arms around our shoulders and posed for a picture. I happily muttered: “Okay, okay, one picture.” The photographer pressed the button, but the flash didn’t go off, so we had to do it again. When the picture came out, it was doubled, for some reason. They took another shot. This time the picture was good, but where it went I didn’t see, as I had invited our American over to our table. The guy sat down without hesitation. We began to get acquainted. He was called Jackson Nelson Moor, was thirty five years old, and lived in Boise City, Oklahoma. I understood him quite well and explained in a reasonable approximation of English who we were. We had wine left and we drank it. Moor proposed a toast “for friendship”, and I “for American progress”, and then for John Glenn, for Gagarin, and many others besides. Moor’s chest was adorned by a badge with the text “Goodwill Embassy U.S.A.”, followed by something else, and with his name and surname in the centre. He said he was head of a firm involved in the production of haymaking equipment. I asked him for his autograph. He wrote his name and address in a notebook and I wrote mine out for him too. Our table was surrounded by waiters. Jackson took some tin badges of the Empire State Building out of his jacket pocket, along with some simple key ring with an inscription, giving one each to Kolka and me. I gave him my people’s brigadier badge. Then he took out his mechanical pencil, with which he had been writing, and as I had liked it, I decided to cadge it off him. Moor gave me his own, though it turned out not to be a pencil but a ballpoint pen. A good sturdy one, though. He also gave me his visiting card. We drank some more with him, ordering some extra drinks. In all, we were quite delayed by the Americans. Apart from Moor, we were joined by another American, Lloyd Vincent, who was older. He showed us photographs of his daughters and wife, and then had his picture taken with us at the table. Kolka ended up with the photo. He ought to have copies made.

I spoke quite a lot that day, but still, I don’t understand the language very well. I gave Vincent one of my ballpoint pens, but he, the swine, gave me nothing in exchange. Kolka and I ended up forking out 22 roubles there (20.50, rather, but the rest went to the waiter for a tip). It was already two when we got out of there. We had been warned that it is forbidden to chat with foreigners, particularly Americans, and about everything that can befall you. From the Metropole we went over to Red Square. We wanted to go to the Mausoleum, but were turned away by the cops; the first time for having a camera, and the second time for being drunk. Then we walked around the square and went in the Kremlin. They let you walk in freely now. We went up to the Tsar Bell. As the sign says, it weighs 200 tonnes. We had our picture taken against its broken rim, but we were driven off the plinth. Then we went to the Tsar Cannon. We tried to climb a bit higher up there too, but were shooed off again. We managed to get one picture, just the same, though some plain clothes type with an armband grabbed hold of us afterwards. But we made out that we that we were from Omsk to stir his pity, and he let us go. There was nothing else to do in the Kremlin, so we went to GUM. On the way we took another pic in front of the Saviour’s Tower. We only went along two aisles in GUM), but there was nothing in particular there so we went down to the gastronomy section to get wine and leave for Shmidtovsky, because they were already waiting for us there — it was nearly five. I took two 0.75 l bottles of Shemakha.

Coming out of GUM, we went along 25th October Street and through the old town walls of the Kitai Gorod to Sverdlov Square. At its gates we came across a couple of girls, who wanted to make a foursome with us and go off somewhere. We tried to get them to come with us instead, but they wouldn’t have it. Naturally, we could have taken the risk and gone with them, but the women were waiting. They were quite plain faced, made up, but nice, though I myself didn’t look at them too much. Ultimately, we couldn’t agree and separated.

We started to look for a taxi on Sverdlov Square. The taxi rank was empty, and none were passing. We finally managed to get hold of one fellow and he took us off. When we got to the house they were all already there, i.e. both aunts and Tanka. I thought her boyfriend would have come, but he wasn’t there. We kissed the aunts, who wailed about where I’d been and how could I be going to Kazakhstan. They came round, of course, thanks to the wine, and when they found out about the Metropole, the Yanks and the souvenirs, they even scolded us.

The dinner was already ready. We weren’t hungry, but had an urge to drink. Shemakha is a good wine, though red — I prefer white, myself. After dinner we decided to go and see Amphibian Man. It was being shown at the Krasnaya Presnya cinema nearby. Tanka phoned and found out that the film started at eight and that there were still tickets left. We went round with her and got four tickets — Auntie Natasha would have to stay and mind Natashka. Until it was time to go to see the film I had a great old time with her, giving her donkey rides and playing with her. She wasn’t at all shy, and declared up front: “Kotsbuts (that would be me), I want to sit on your shoulders” — and up she climbed. And she had a right sly little face about it.

Then we went to the pictures. At the time we had to leave there was still twenty minutes left to go. It’s a good film, as I already said. When we got back, Auntie Natasha did us a favour by inviting me and Kolka to stay at her place on the Lenin Hills, where her flat was near the Mosfilm studios. She wanted to leave us there while she spent the night at Shmidtovsky. We got there at eleven. Auntie had told us where everything was, told us to brew some tea, and made up our beds — me on the couch, and Kolka on a foldaway bed. To not worry anyone, she wrote a letter to the neighbours and left it in the kitchen, and informed some of them, more reliable than the others, — there is a young unmarried woman living here — in person. This Galya was having some kind of party, foxtrots blaring away, and there were a lot of people talking. She was pretty decent looking herself, in trousers, and I fantasised — perhaps we’d be able to sort something out after a drink. With this in mind, I even went to go boil the kettle in the kitchen, to make her acquaintance, but although the guests had gone by then there was still one guy hanging around, almost my height and built like a boxer, who was obviously living together with her. I was immediately crestfallen, and had to go and take the tea off the stove for nothing. I sat up till half one writing my diary, and even so I didn’t manage to finish, though I’d almost sobered up entirely. In any case, I hadn’t been very drunk, though the effect had been felt.

Car Crashes of All Years

14 pictures, 1972–1981

24th July 1962 Tuesday

Kharkov

Finally, the weather today turned out nice, sunny and warm. Admittedly, there was a sudden downpour of warm rain at four o’clock. But this was pleasant anyway.

I got up at ten to eight. I washed, dressed and went to my café over the street. I had pelmeni, and a cucumber salad, kefir and a biscuit. I paid 65 kopecks. After eating, I boarded a tram and went to the polyclinic. I got there a little before nine. There was a crowd humming in the corridors and foyer. There was supposed to be a demonstration of how to stop stuttering in the conference hall at nine, where all the clients should have been gathered. But the doctor hadn’t turned up yet so everyone jostled to find what place they could. Finally, Vivdenko arrived. The hall filled up and they almost had to turn people away — there were parents bringing their kids, the kids themselves, and all manner of other sufferers. The little doctor announce that he would now carry out a single-step session on the curing of a stammer, and took ten people from the group who had registered for this six to ten days previously. There were two very small boys aged around ten, three girls of thirteen to fifteen, and some lads under twenty-five. The essence of it all, of course, was hypnosis. A women doctor then spoke about the causes of speech impediments, really hammering it into their heads. Then they started mesmerising them, looking intently into their eyes and placing hands on their head, making them fall forwards and backwards, though not to the floor, of course. Then she took two of them — for the sake of time — and put it into their heads that their arms had been amputated, then lifting their arms and making them splay their fingers. And there they stood, until she brought them out of the trance. And then she began her final trick — freeing them of their stammer. On the count of “one-two”, the lady doctor, according to her own assertion, summoned up an explosion in that part of the brain cortex which governs speech. And several of them really did begin to speak properly, some a little worse, and one, whom it had been hard to hypnotise, didn’t show any change at all. All ten persons answered various questions before and after the session, and the difference was apparent. After the session, they were all instructed to keep silence until the next morning, in order to strengthen the reflexes in the brain and give their speech centres rest. Then there was a fifteen minute break, during which I ran for a newspaper and some ice-cream. After the break, there was a control exercise or test of those who had previously been hypnotised. There were twelve of the most varied kinds of people, including several more mature women. Most were young people between the ages of twenty and twenty-five, though. And here there were different results. They were all made to say various things, to ask questions of each other and the audience, i.e. the parents and “us”. At the end, Vivdenko said that those who had registered on Saturday and Sunday could stay today for a preliminary examination. The rest, who had registered on Monday, would obviously be examined tomorrow. And above all it was necessary to go to the sessions and control sessions every day, which was absolutely vital.

It was almost three by the time I went home. I’d left the newspaper in the hospital, taken my glasses and gone into the centre. I decided to buy a ticket for Seven Brides … at the First Komsomolsky cinema on Sumskaya, and then go to eat. I went to the cinema on foot, left at the Univermag department store, beside the huge bell tower, visible, most likely, from all parts of town, through the garden square where the Eternal Flame burns at the memorial for all who had fallen in battle for October. The garden squares here are beautiful, tidy and clean. And the town in general is nice. The only thing is the ditch in the centre (this is the River Kharkov, apparently), which smells something putrid. At the cinema, I came across a decent sized number of people for the showing at five. I stood there for twenty minutes, the ticket booth didn’t open for ages, and then I got a ticket for fifty and went to find an eatery. I found one not too far along the street, on the same side. I got “cold borsch” — something like okroshka, but red in colour, and quite delicious! — a cutlet, cucumber salad, blinchiki and compote. I ate unhurriedly as I had plenty of time. To fill it, I went to the barbers — I mean perukarnya, in Ukrainian. I was shaved by a rather pretty girl, who I stealthily began to chat with, to wheedle out of her whether she had a boyfriend or not. Turned out no, and that, even in a big city like Kharkov, they don’t hang around, and she was afraid of walking alone. I made a mental note of that, and found out too that she finishes her shift at eight, so I decided to come along then — maybe something would come of it. She shaved me very delicately and stroked my cheeks, and so I was getting quite turned on. Then again, these chats and caresses set me back seventy kopecks, and a carrot-lipped blonde then came along to do my neck, and spray the naikraschy eau de Cologne, as I put it, into my face and hair. Leaving the perukarnya, I walked off in the direction of the cinema, read the newspapers in a shop window (they don’t bring today’s national papers here, they print them in Kharkov from a template flown in by plane). The Komsomolsky picture house is quite modern, with two screens and a luxurious foyer, buffet, toilet and other comforts of civilisation. The film was in colour, widescreen, produced by Metro Goldwyn Mayer, USA. It was a comedy, of course, with wonderful colours and exaggerated fight scenes, and was pretty good on the whole. But I’d enjoyed Ghosts more, and would go to see it again, which I can’t say for this one. The plot was about how seven lumberjack brothers, living in the mountains in Oregon, not seeing town for five months at a time, got married. I’ll have to try and see the panoramic film Dangerous Turns next, which they were advertising as “a world’s first”. The film finished at twenty-five to seven, and I went home to write my diary and then dash out at eight to catch my hairdresser. Lately, women have been stirring a painful attraction in me. And at the dacha in Podrezkovo — I thought I’d have a rest, but Rina was distracting me all the time. Yet in Kharkov I caught myself several times walking along the street and looking at and weighing up women. And, actually, there is plenty to appreciate here. And the women are all plum and well-built, mostly with nice faces too. The kind of crocodiles you get in Gorky or Moscow are scarce here.

Having got to the hotel, I went up in the lift and sat down to write my diary, there are new residents here every day, and I rarely see them. I didn’t manage to write much — the radio was bawling and it wasn’t easy to turn down the volume — maybe the others are listening to it. At half seven I went to wash, dried off, being all sweaty, and ran for the tram. I would have been in good time, had I caught the 11, but it had just gone, so I had to walk to Proletarskaya and get on another. At five to eight I paraded past the hairdresser’s — “mine” was still there. I stood nearby at first, then crossed to the other side of the street to watch better. I was standing there a good long while, twenty-odd minutes. Finally she came out. I followed, and then crossed to her side, getting ready to catch her up. But then somebody went up to her, unceremoniously took her bag from her hand, put his arm around her, and led her down a side street. With a nonchalant air, I put my hands in my pockets and walked past — there was nothing else I could do. My Kharkov romance started and ended there. After that, everything was dull and grey. I got on tram 11, went to the hotel, went up to my room, changed, and sat down to write my diary. Then I went to wash for bed. I lay down to sleep at ten.

15th August 1962 Wednesday

Podrezkovo

A sunny day, but chilly, due to the strong north wind. Towards the evening it quietened down and it got warmer. At 21:00 it was 11 °С out on the balcony.

I got up at ten and went to wash. During breakfast I suddenly heard a howling from the radio speakers, like Pinocchio speaking out of a jar, the voice of Levitan: “All radio stations of the Soviet Union are in operation! You are listening to a TASS broadcast!” and the jingle began squeaking away. We caught on right away that one or both cosmonauts had landed, but old Abrasha was agonisingly formal. They soon reported that both had landed south of Karaganda. Vostok-3 had completed 64 orbits around our sinful planet, travelling over 2,600,000 km, and Major Nikolayev had been in flight for 95 hours, i.e. four days minus one hour. They had landed at 9:55. Vostok-4 had completed 48 orbits, clocking up around two million km, with Lieutenant Colonel Popovich having flown for three days — 71 hours. He landed at 10:02. Those Ivans have been working hard, a great deal of resources pissed into the wind…

I did nothing of any use to society today and more or less spent the day twiddling my fingers. After breakfast I went to sunbathe, taking advantage of the sunshine, having almost lost my tan completely since I’ve been knocking around here, clothed all the time.

In the clearing, in a sheltered spot where there was some hay, I made a fire and lay down. The sun warmed me nicely, but now and then the wind, breaking through the bushes, would blast me so hard that I came out in goose pimples. Natashka and nephew Alyoshka came to do somersaults there with me. Natashka, thank God, soon lay down to sleep. Alyoshka is a big boy, twelve years old, has moved up into the sixth class, and I talked with him about various topics, mostly about technology and space. Then he went off too, and I started reading Blettsworthy.

I lay there almost four hours, changing places a few times as the shade of the birch trees crept up on me. They then called me to dinner, a bit early today, as we usually eat at six or seven. After dinner, I looked attentively through the albums Auntie had brought yesterday from Moscow. One was ancient, with all the ancestors in it, with our old people there aged just 3 to 15. The second one was mostly pre-war photos from Podrezkovo, with me and Tanka playing a major role. There were lots of pictures with Granddad, and we haven’t got any. And we have none of me in the kind of pictures they have here, either.

Alyoshka soon came back, and me and him played ball until we were worn out, a bit of basketball, a bit of rugby, and a big of devil knows what. I was sweating like hell, and gladly went for a wash under the tap. Tanka’s friend Lida came along, who I remembered dimly from 1952–53.

At nine, I wrote up the day’s events and read Mikhalkov’s Uncle Stepa to warm up. I then ate a little, drank tea and, as usual, didn’t go to bed before twelve.

24th August 1962 Friday

Kadnitsy

It was wet and cold in the morning; then the clouds dispersed and it became sunny and warm, but it became overcast again in the second half of the day, turning to rain by evening. The radio had promised inclement weather in Moscow.

I got up at half ten. I washed, and drank coffee. I had to go and fix the motorbike, but I wasn’t in the mood to go out at all in this weather. But I had to; first, though, I would have to get my clothes ready. I wasted time getting a bottle of rum out of my boot, which had been shoved into it back in Chelkar when I’d sent my bags by freight. I almost couldn’t get it out. Then I went to call the post office to see if a letter had come. I thought there simply had to be a letter from Ivan Kartashov, and that it was quite likely I’d have one from Sashka Shvidkin too, and maybe a transfer of five roubles off Vaska the Petersburger — if he had any conscience in him. It was highly unlikely I’d have anything off Lilka Kantsedal. The post office people said there was one letter, and that the girl from the children’s home was bringing it now, with all their correspondence. Well, it’ll probably be off Ivan, I supposed. Then, when I was screwing the boot protectors onto my boots, the letter came, and Mama, who handed it over to me, said that it was from Kharkov. I was astonished. The one I had least expected had come. The address was funny: “To Kozakov (for Nikolai)”. Silly girl! I opened the envelope without trepidation, though I guessed, and was inclined to believe, that it was probably a request not to bother her with any more letters; on the other hand, however, the return address had been written out carefully, indicating the number of the postal division. But there was no more guessing as I had taken the letter out and started reading. It amazed me. In the first few lines, Lilya asked me to forgive her for being the way she is, i.e. that there should not, as far as I understood, be drawn any equal sign between her and Artemis, and for the fact that she had passed herself off as something she wasn’t, and had behaved like a silly girl. She wrote that she had longed for my letter, but that it had only arrived on Sunday evening, and thanked me for the telegram, thanks to which she had had the opportunity to write to me. Well, plenty of words, as they say, with the general sense that she ought to have written to me, else it would have played on her conscience, and so on. There were a lot of exclamation and question marks. “I, — she says — simply don’t know you very well, but I hope that my feelings don’t deceive me.” Well, and then if I was fine and how my trip had been. At the end, she wrote: “I will wait, too. Don’t be cross. I beg you. Until next time! Lilyok.”

As for what all this meant — it was puzzling me all day, and seemed likely to do so until her next letter. Allowing that all this be true, — why would she have written that she was “the way she was” if it wasn’t true? People don’t normally write or speak about such things until there’s nothing else for it. That she is very truthful, honest and simple? But then she would have been fully capable of seeing me, if she’d wanted to — and gone to the clinic on the Monday afterwards. Yet she wasn’t obliged to go and visit my aunt, as she writes. And a letter sent on Friday evening can hardly have reached here, in town, in just three days, while her letter was sent on the 13th, and was already here on the 15th, could it? Perhaps she had hesitated a long time, perhaps she’d been anxious, and not been able to make her mind up what to say? And why does she trust me like this? Of course, these are probably all the whims of a female heart, and no reason to make any strong assumptions over. It should all become clear once and for all after her answer.

I wrote her a reply eight pages long — there you have him, the failed man of letters! Firstly, for the sake of full clarity and mutual understanding, I told her that it hadn’t only been her who had burnt her fingers, as she had said, but me too, and the worse so for being married (all the same, I said nothing about alimony). Well, I went on about the same topic a bit further, i.e. that I dreamt about her, about how I had worried in Kharkov, and how I want to see her and so on and so forth. I wrote in detail about my travels and about how Mama knows about her and sends her greetings. I asked for a photograph and sent her one of my own from Kazakhstan — one of me with a ZIL and a whip. I addressed her very tenderly, of course — zironko moya, shchiro sontse Ukraini, my darling Khokhlushenka…

I have run on ahead of myself here, as before I sat down to write, I’d screwed the boot protectors on and patched up two holes in my cotton breeches, had dinner, noted and registered my new books and records, put the table back in the old position, and tidied up everything on it. Altogether, I sat down to write at four. And yes, I went over to see Maria Ivanovna Uspenskaya too, wanting to try and get the motorbike going, but she wasn’t in.

In my break from the letter I had lunch — Mama boiled some potatoes and cauliflower, brought a salad from the kitchen, and filleted a few Aral Sea breams. You really ought to open a bottle of something to go with such a delicacy, but for some reason it didn’t even come into my head. I can’t have reformed myself entirely, surely, like with the tobacco, can I? It would be good, not to want to go boozing so. If ever I have to drink — fine, I’d drink — but it would be nice to not want to drink otherwise.

I finally caught the cat today, which had gone quite wild, the poor thing, and wouldn’t even come when beckoned. They said that he’d eaten somebody’s chickens. I don’t know about that, but he does have quite a belly on him, and is missing a fang in his bottom left jaw. Dreadful looking, missing a lot of fur, the poor thing. I gave him some milk and a bit of sausage. Once I’d written and sealed the letter — I had asked her to write to Mama without a return address, to satisfy her curiosity a little, and when I get work, if we carry on our correspondence, that I would tell her where it would be best to send her letters — I took up my diary. So I spent half the day writing.

Nothing will come of the motorbike tomorrow — it’s going to rain, but I’ll have to go to the RZhS to charge the battery and deliver the letter. It’s interesting, nevertheless, to think what will become of my romance. It would be nice to be a clairvoyant, to know at least whether a person is like they would have you believe, or not. To the devil with them, these women, maybe she’ll laugh at my letter and show everybody — look at this sucker, thirty years old and married, with no sense to show for it.

Having finished my diary, I lay down to sleep at just after midnight. And that after putting myself to a strict regime of going to bed no later than eleven, ideally at ten.

Zaprudnoe, Moscow. Part Two

19 pictures, 1970

7th October 1962 Sunday

Kadnitsy

It was a sunny day, but I don’t know anything beyond that, as I stayed home. In the evening I’d set my alarm for seven, but what the hell would I be like, driving today? I felt absolutely shitty, sick, and, half dozing, half just lying there, stayed in bed till four in the afternoon. But it was for the best, as I recovered completely and even worked up an appetite. So, my day began at 16:00.

I washed, Mama fed me some fried duck that she’d made yesterday, I drank coffee, and set about my tasks. First of all, I cleaned up my trousers and jacket. You can’t avoid doing the laundry, clearly. Then I took my diary and went to write in the office, while Mama was listening to the radio.

Yes, actually — I am forgetting everything: on the 3rd October at 17:28 New York time (0:28 in Moscow), the spacecraft Sigma-7 had landed in the sea 275 miles to the north-west of the Midway atoll in the Hawaiian Islands, 4 miles ahead of the aircraft carrier Kearsarge (which had, in March 1960, picked up four Soviet soldiers who had been carried away out to sea on a barge). The astronaut Walter Schirra had flown for 9 hours 12 minutes, having made six loops with a maximum distance from Earth of 176 miles, i.e. higher than our Nikolayev and Popovich, — whose apogee had been 251 and 254 km, to Schirra’s 282. Well, thank God. Our Shark sent a congratulatory telegram to Kennedy, giving both him and Schirra his best wishes.

While I was reading these articles in the newspapers, Faika came. I had to hide the diary, though she wormed it out of me that I’d been writing. I led her home. At eight, she ate with us, finishing the duck and drinking tea. Then she left, and I went to the workroom to finish writing. It was terribly draughty there, though, and I came back after eleven. I went to sleep at twelve.

1st November 1962 Thursday

Kadnitsy

The weather has already turned for the worse. Although it’s warm, it’s started raining. It had rained last night, and rained several times today. It’s getting muddy. A south wind was blowing.

I got up at quarter to ten. Having washed, I sat down to breakfast. I had roast potatoes and drank tea. Mama had already gone out, and I began to get out and dismantle my hunting gear to put it away in the case I’d prepared for it. I found that my gunpowder was out of date — it’s from 1956 and 1958, and the shelf life is only four years. Yet it would be a shame to throw it out — there’s one untouched tin of 200 g, and still a bit left in the 100 g one.

I took a book by Markevich, clearly a big expert on weapons — Hunter’s Ordnance. It says there that smokeless powder should be perfectly fine for around ten to twelve years if kept in storeroom conditions. So I’ll use it to shoot. Only old bullets need discharging and recharging again. And the rifle ought to be tuned to see which cartridges are best. It’s been a long time since I used the gun, but I ought to take it up again. Better to spoil 15–20 bullets, but get the best result in the end.

Fiddling about with all this, I found five packs of photographic paper in the table where we eat, two of which were completely untouched, along with my bullets, development liquid and fixer solution. These were from 1957, when I had had my last fling with photography. I should give them to Kolka Sukhanov, maybe they’re still fit for use. I also found some envelopes there with negatives from 1953, ’54 and ’57. I looked at a few. How long ago it all seemed… Everything has changed, yet the photo emulsion still bears the traces of the past. There were even a few negatives from Tolba, made from the 1948 Komsomolets of blessed memory.

That was how I was fiddling around, dredging up old memories. I went to dine at around one, called Mama, and sat down to eat. Afterwards, I carried on with my equipment, read some more of Markevich’s book, and measured the diameter of the shotgun pellets, to ascertain the gauge. For some reason, the gauge had to be reduced from the old specifications. Once I’d put everything in the case and tidied up, I sorted out the cartridge belt, whose end pouches had been lost, and I had already lost three bullets from it. Having done this, I wrote up yesterday’s entry in my diary, as it was already around four o’clock or more. At half five I went for dinner. It was cutlets. We ate, and I went back to writing. When I’d finished, I read Knowledge is Power. I got hungry again for some reason, and towards ten Mama made some toast, and I had them with two mugs of tea. I read the magazine and listened to the radio. They’ve renewed the blockade of Cuba. After finishing my diary, I lay down to sleep at half ten.

6th November 1962 Tuesday

Kadnitsy

A perfectly cloudless day, but cold all the same. There’d been a strong frost in the night, and there was a hoar frost, which then melted, getting all slippery and muddy, but then it dried up. The sun was nice and warm, but out of the sun, I repeat, is chilly. There was no wind.

I got up at nine. I washed and had breakfasted. Then I shaved. I took a new razor and cut myself all over, like a real messy little pig. I was in a foul mood right from morning. There was no chance of any poetry today. I sat on a chair in the middle of the room, puffed up like a horned owl, fixated on one point. The day carried on as badly till lunch. In the afternoon, I was going to go to Kstovo — to find out if a letter had come from Lilka, and to send one to the commissar. But first I had to eat. I went into the kitchen. Mama was sitting in the office, writing something, and I ate alone.

At a quarter to one I left the house and set out for Zaprudnoye. Just in case, I took with me my savings book, documents and, of course, the letter to the Kharkov chief of police. Trusting in the sun, I went in boots without galoshes, but it was very muddy in parts. And in the forest, out of the sunlight, there was still hoar frost falling. By the forest, in a glade where we all used to sit, with Sukhanov and Golovanets or Loskutov, there stood, all in a line, two Volgas and one Pobeda. A bonfire was smoking away. Kids were running around. Aye, this sort had a nice full life, of course. They might have filmed them for Khrushchyov’s cinema or written about them in the newspapers. Imagine them taking a picture of me…

When I started going down to Zaprudnoye, I saw a ZIS-155 stopped at the auto station, i.e. the Kstovo bus, as there are no other buses here. I broke into a run and carried on with an orderly dog trot. I rushed right out onto the road. An Ikarus was driving along too, but it was full, and they even stopped. I’d just got up to them when the bus started, but the driver saw that what a presentable gentleman I was and slowed down to let me on. There were still some free seats left. The Zaprudnoye lads were on board — Vitka Chuprunov and Borka Chadayev. I got a seat for the moment, but Borka soon had to sit with a child on his knee, and then it filled up with crematorium clients. Another friend got on too, Slavka Tarakanov from Vyyezdnoye, and we all chatted with him. He works in Gorky, and wants to buy a car — a beaten up Opel for 200 roubles. After the conversation we arrived inconspicuously. Since yesterday, the bridge had been reopened to traffic (after a car had got completely smashed up there), and the exit road over the old one was blocked off.

We got to Kstovo at quarter past two. I immediately caught a town bus to Kstovo Station and the savings bank. I got there, but it was shut. I then went to the communications office to ask if a Kharkov letter had come. But, it hadn’t. After this, I returned to the local shop and took the bus back into Kstovo again, to go to the post office. I’d thought that they were at lunch until three, but today they’d clearly kept going without a break, so it was open. I handed over my passport and kept the letter to hand, to send by recorded mail if nothing had come for me. Suddenly, I saw it, an envelope from the bundle had been put inside my passport. There it is, they said. I looked — and it was from Lilka! This meant I’d scared her with talk about the police.

When I was opening it, my knees were shaking. Catching my breath, I opened the envelope. Well, she’d written all kinds of crap. Again she asks forgiveness, says that she has scrutinised herself, that I am a very good person, but she simply cannot love me because she doesn’t know me, and there’s a lot you can’t discover from letters alone. She is right there, of course. It’s a pity, she says, that a large distance prevents us from talking face to face. But even so, you are a very nice man. Why, she asks, do you love me? You don’t know me, you saw me only once, and I have done so much to offend and disappoint you. Perhaps, she says, I will discover that you deserve more feeling, but I don’t know now what is up with me. Tell me, what should we do? The most important thing is that I am scared of causing any pain to your girl. I want, she says, for us to remain good friends. Can’t you forget about me? Write me, she says, about everything. Well, and that’s it. There’s the cut, as they say.

I read and started smiling. Fate had not left me with nothing to celebrate. Something modest, but something nonetheless.

Reading this letter, I shoved the letter to the commissar deeper into my pocket and went to the bus station. Well, what actually was there to do? I decided on this: I will write to her, just not immediately, but with the aim of going to Kharkov. To see what she thought of this idea. Not necessarily as her lover, but just to be closer to one another. Fuck them, I can’t live with Faika anyway, and maybe this is a way out. And if not, then fuck it anyway. Alright, I’ll write to her after the holidays. But if she gives me the run-around again… I’d already decided I’d meet the New Year in in Kharkov if that happened.

While I was thinking it over, I came to the bus station. The bus was going at 15:35, and it was 15:10. I went to the crossroads. There was a fierce-looking flatfoot walking there. I stood away at a distance. In five minutes, a GAZ-63 pulled up. The cabin was empty. It was from Rabotki, from the dairy factory. I lifted my hand and got into the cabin. The driver was one of our gang, Lenka by name, though I forget his surname. We were talking all the way there. Thankfully, there was no hold up at the new bridge and we got there in twenty minutes. At twenty to four I got out at Zaprudnoye. I gave him thirty kopecks, but Lenka turned it down indignantly. So there is still conscience left among Russians. I hobbled off home.

Past the forest I saw an animal on the road ahead. A fox or something. The creature let me get within 70 metres and then fled into the field. It had a long bushy tail and was red — aye, just a fox. It sat down in the field 50 metres from the road. I shouted, whistled, beckoned and waved my arms at it — it watched me but didn’t go any further. I went on, and it went back onto the road and ran off towards Zaprudnoye. If it was a fox — why would it run along the road? If a dog — why was it scared of a man?

I got home at twenty past four. I had to go and see Kolka Sukhanov, though. I went over, but there was nobody in — they’d gone to the pictures. There was just Anna Pavlovna and Pavlushka sat down below. I sat down too to wait. The Sukhanovs came at twenty past six. I waved Kolka over — well, how about wetting our throats, eh? Aye, sure, I wouldn’t mind. We soon ran over to the shop. They had moonshine, Moskovskaya vodka and 50%, champagne and Buck’s Fizz — for two roubles twenty kopecks. We decided to get the Buck’s Fizz and four vodkas. We also took a jar of Khrushchyov’s vitamins — some sea kale, and a herring. The Sukhanovs live with a father in law so we had to treat him too, but he’s a good old fellow, sociable and disaffected with the Socialist regime. Incidentally, before the drinking, Kolka showed his son a slide film and I watched it too. Though we were four in all, we had to drink twice, and it was something pretty awful. But we drank it anyway. Not having any crab, we chased it down with seaweed. A godsend, full of iodine. You won’t come down with goitre, anyway. As is the done thing, we began praising the existing socio-political structure, the wisdom of the Shark who had preserved peace, and our incredible state of prosperity. They don’t give out loaves of bread over 2 kg, so we reckoned up how much they must have taken. The Federation alone had produced 2,212,000,000 pounds’ worth. Glory to the Lord!…

Of course, the Buck’s Fizz wasn’t quite champagne, but it was alright. You don’t need anything more for just two people. We drank, sat around a while, and at eight I made for home. Kolka accompanied me. I invited him to come over tomorrow. After dinner he might be going to the weir, but he wanted to come over in the morning. We’ll ride to Kstovo then by motorbike, and take a hair of the dog that bit us. When I got home I took my diary and went into the office, but Mama was doing the washing. I helped her hang out the linen. At eleven, once I’d finished with my diary, I munched on something and drank tea. At half eleven, I fell into the embrace… not of Lilka, but of Morpheus.

12th November 1962

Monday

Kadnitsy

Overcast today, with an unpleasant wind blowing from somewhere off in the eastern territories. Drizzle. The occasional bit of rubbish flying about. Br-r-r!..

I got up at quarter to nine. I didn’t want to at all, and Mama urged me to have a lie-in, but I overpowered these petit-bourgeois instincts and heroically bestirred myself. I washed and had breakfast. At half ten, Mama hauled anchor and I sat down to compose some verses. I inspected my lines carefully, discovering that they could, in the main, be left as they were, save the exception that I didn’t have enough lines for the fifth part. I’d think up something suitable and that would do, basta. There ought to be eight stanzas, all logically interconnected. To make a start, I wrote out the full quatrain in order, just leaving an empty space, and began to correct it. There weren’t many corrections to make, so it was all more or less licked into shape. For the fourth part, I had three alternative versions, and, hacking away at it, I ended up with a perfectly decent combination of characters: “Darling, open your heart, look into the bright distance: happiness awaits us there, you and I, in the glimmer of a vernal dawn!” Then I began to think over the non-existent fifth line. With the expenditure of no terrible mental exertion, I crafted something appropriate: “Why do you lower your gaze, seeing my bashfulness? For I have spoken unto none other hereto: ‘I love you!’” It was just that this “bashfulness” would better have been put as “discomfort” — which sounded far better. By dinnertime the poem was ready. I ran into the kitchen, and was served boiled macaroni. I ate up, and after two I set about a new task — writing an accompanying letter to send to the editors of Kharkivshchina, to which I’d decided to send my lyrical offspring, and… to Hasan-Kuli!

During the last few days, I’d been reading a brief piece in Around the World on the Hasan-Kuli nature preserve, on the eastern shore of the Caspian Sea by the border with Iran. And I had resolved to write to them there, to inquire if there were in need of anyone like myself. It’s warm down there, that’s why. Close by is Kizyl-Atrek, and there are fig palms giving fruit there, cactuses, and the burdocks grow tall.

Having given up on the rough copy of both these formal letters, I started writing to Lilka. I suppose, reading the newspapers, that I would send them a poem I’d been inspired to write only thanks to your letter. I wrote too about how I’d spent the October Revolution holiday, and how I’ve been getting along in general. I wrote her today just as a close friend. Devil take it! So, I think about her, I think, and it seems that something ought to come of the two of us. Not exactly that I had found a new confidence, but rather that my subconscious or something was confirming it every day. I am scared to trust in this, scared to be at peace, to surrender myself over to the rule of intuition. Objectively weighing up the pros and the cons, I mercilessly crush all these brittle hopes. But in my heart something once more speaks out against it, and there come an assurance and sweet solace.

Once I had written to her, I sealed the letter and went over to Mama at the typewriter. I looked over the drafts of my formal letters again, edited them and began to type. I made copies for myself too, as a memento. I didn’t manage to finish the two of them, and had to go for supper. It was cutlets. I ate, drank tea, picked up the typewriter and all my stuff and went into the office. I finished the letter to Sotsialistichna Kharkivshchina too, without hiding the reason why I was sending it, — well, there’s a girl there, she might read them.

I don’t know whether they’ll print it or not. Of course, they ought to, it being from a guest of Kharkov, and one in love to boot. I then began typing up the verses. I checked the manuscript one final time, but couldn’t find a thing wrong with it. I put the paper in the machine and started tapping away. I made two copies of three pages, i.e. six sheets in all. I sealed one original in an envelope for the Kharkov lot, and placed one for myself in my album. The copies were in their places. Having finished my typing and letters, I put everything away and went to write my diary. I was doing this until ten, whereupon I went to drink another mug of tea.

I’m going to Gorky tomorrow, to send off my correspondence, to find some decent paper and exercise books, and might go to the police station and say — well, could you help me? In general, I don’t know what to do about work. I can’t depend on Kharkov, never mind Hasan-Kuli, of course. It would be folly to sit with my mouth open and wait until they invited me. But wouldn’t it be nice to go to Kharkov! Oh, God! She’d somehow made me her own, the damned Khokhlushka, devil take her!

31st December 1962

Monday

Slobodskoye

Frosty, without precipitation. Anything else, I don’t know.

I got up at ten, though I woke up a little earlier. I’d slept rather badly — it might have been the couch being too small, with my feet hanging over the edge, and it was pretty cold. Lilka hadn’t come to me in my dreams, either — and that also played its role.

Lyoshka was already on the bed in the morning. I told him that Sergei had ordered us to come, so we dressed quickly, washed, drank 50 g each of what was left of the Rubin, ate a pie each and went to the school. It was all locked up, and we went straight to Sergei. But then we saw him, coming to us. He called us to him, but we supposed that first we should take something to drink and then go. Sergei gave us a fiver and told us to get a Rubin and bring back the change, so we went for nothing. Me and Lyoshka then went into the shop while Sergei was cooking something to eat. We met Severyanych. He was coming out of the boarding-school (he’s a tutor there or something).We shook him down for the loan of two rouble coins and one rouble note. He said that he’d be in the industrial goods shop, and we went to the grocer’s. We got a bottle of Moskovskaya and a Rubina. Then we went to pick up Severyanych and walked to the post office — to phone to Kadnitsy to see if Vovka had come. We hoped that, being the worse for drink, he’d ran to sleep it off at Valka the paramedic’s. I was calling, but nobody answered. Severyanych then got through to the children’s home somehow. Mama answered. What, she says, you’ve lost Vovka? Turned out they’d found him in the morning, sleeping in the hall (possibly after a passionate night of lovemaking…). Well, sod him. The main thing is that he’s alive and well. He’d gone out, she said, an hour before to meet us in Slobodskoye, with all his things. Well, we’ve have to take a fine off the lousy son of a bitch.

We’d just got to Sergei and had started to take our coats off — when our offender flashed past the window. He’d got here already! Vovka was confused and eagerly acknowledged his guilt. We sat at a table where potatoes were sizzling on a skillet, with garlic-cured salo and cabbage. First we drank the vodka, which I took better today than yesterday, chased it down with a bite to eat, and then we started on the Rubin. At twelve o’clock we accompanied Sergei home. He went along the path between the shop and the boarding-school, and we went back to our offender, who coughed up the money without resistance. It wouldn’t have been an easy task now to get hold of any vodka, however, as the place had filled up with people, with guys on the street thirsting to quench the fire in their raging souls. Severyanych, using his prerogative as member of the shop control committee, managed to get through the back door somehow and brought a bottle of special brew with a chunk of semi-smoked sausage. We went to drink in the boarding-school, which was empty over the New Year. As Dyrkin told us, there had formerly been a beer house in this building, which had many times been attended by his father as a client, when he had been working as a teacher in Slobodskoye. This was forty years ago, of course. We took our positions at the table, and turned on the Rekord radio receiver. Severyanych ran round to the neighbours for bread, and I peeled and sliced the sausage. We drank, ate, sat and went home — we, i.e. Lyoshka, me and Vovka. As though to go to bed, but really to give Severyanych the brush off so we could go and polish off the Dubnyak, for we still had one bottle left.

When we arrived at the Nuyanzins, they were already waiting for us with a supper. Nina Mikhailovna poured out hot cabbage soup with pork into bowls. The Dubnyak was also brought out, of course. Once we had drunk it, we were soon in the mood to sing something. I sang with Lyokha, while Vovka tried to photograph us in the light of a luminescent lamp. Even if the flash had been enough, Vovka could hardly have been in any state to take a steady shot…

After supper, Lyoshka ordered us all to sleep. They made up beds for us by the stove and gave us pillows. I didn’t want to sleep, and Lyokha too was more inclined to singing, but he reckoned all the same that we weren’t fit to bellow until midnight, and it was only four. For two hours, however, me and him sang by the stove — Vovka had nodded off.

The women prepared the ingredients for future pelmeni. You can sing a lot in two hours. In the song Farewell, Dove, when we reached the words “It fluttered right out of our hands, the years of childhood have left us”, — me and Dyrkin wept, but a few minutes later we were already belting out Bandit Leningrad: “The Crook with Smarts is an interesting song, ha-ha!..” Finally we quietened down and fell asleep. I didn’t notice when or how Severyanych turned up, but he was with us on the floor later, when we woke up.

I don’t remember what time we got up. But it was already time for speeches. I suppose it was around nine or ten. We turned the television on. Congratulations on the coming New Year beamed from the screen. There was a broadcast of At the Blue Light. There were speeches from Kibkalo, Kobzon, Eizen, Troshin, Ots, Rudakov and Barinov, Raikin, Shulzhenko, Dorda, Zykina, and many more. That was what I saw. But I wasn’t sitting watching the screen. On the orders of her husband, Anka had set aside a litre of Moskovskaya in good time. The traditional dish was served — pelmeni. But I took something the wrong way and ran off twice to be sick, though after that I was once more avidly knocking back the vodka. Finally it drew close to midnight. The solemn moment came, but it was very sad too. Not because yet another year had passed by, but because I was sitting there alone, Lilka was a thousand kilometres away in Kharkov, and I didn’t know who she was with, where she was meeting the new year, or if she was thinking about me. Aye, that was more or less how it was…

The text “Happy New Year” flashed on the television screen and some soft music played. The chimes rang out. I took the champagne, opened the bottle and filled the glasses. We drank the wine to the sounds of the anthem. Then we sang a little more, but it was already without strong enthusiasm. We drank tea. The television broadcast was still going.

We lay down to sleep as soon as two o’clock. Vovka and I slept by the stove. Everything was fine and we weren’t terribly drunk. Lyoshka said that we’d sung badly today because we were too lazy to move our lips. Perhaps. But in general, although it hadn’t been a bad holiday on the whole, I’d enjoyed it more on the October holiday, despite my sorry appearance and suffering from alcohol abuse. We’d sung well then. You really ought to sing on until four at least! But it hasn’t been bad today.

The holiday came to an end, the year 1962 passed, and nothing had changed. We just pulled another sheet off the calendar… And we never got round to dancing. It’s a long time since I danced. Incidentally, something about last night’s drinking didn’t so much cheer me up as sadden me and spoil my mood in general.

Kadnitsy. Zaprudnoe. Kstovo

K. Glushchenko, 21 pictures, 2016

НИКОЛАЙ КОЗАКОВ. ДНЕВНИК. 1962

Звукорежиссер К. Глущенко

Диктор Ю. Ковеленов

Редактор К. Чучалина

Технический редактор Т. Леонтьева

Звукооператоры: С. Авилов, Р. Хусейн

Арт-директор: К. Глущенко

Иллюстратор: А. Колчина

Дизайнеры: А. Глушкова, А. Московский

Сайт разработан на платформе Verstka.io

NIKOLAY KOZAKOV. DIARIES. 1962

Director K. Gluschenko

Speaker Y. Kovelenov

Editor K. Chuchalina

Technical editor T. Leontyeva

Recording engineers: S. Avilov, R. Khuseyn

Art Director: K. Gluschenko

Illustration: A. Koltchina

Designers: A. Glushkova, A. Moskovsky

Site was developed with Verstka.io

Запись произведена на пленку Quantegy на 24-дорожечном аппарате Studer A820 с использованием

микрофона Neumann U67.

Recording is made on Quantegy tape with 24-channel

Studer A820 using Neumann U67 microphone.

© ГЛУЩЕНКОИЗДАТ, 2016–2017

Студия звукозаписи „Параметрика“. Запись 2016 г.

Проект подготовлен совместно с фондом VAC

в рамках выставки „Прекрасен облик наших будней“

Заказ № 153. Москва, Северное Чертаново, 2017 г.

Order № 153. Moscow, 2017

© GLUSCHENKOIZDAT, 2016–2017

Recorded in Parametrika Studio in 2016

The project was prepared jointly with the VAC Foundation within the framework of the exhibition

"Our Days Are Rich And Bright"